Blog

Genetic Cancer Screening: What You Need to Know About Risk, Testing, and Prevention

Genetic cancer screening is transforming how we think about cancer prevention and early detection. Rather than waiting for symptoms to appear, people can now understand their inherited risk for certain types of cancer and take action before the disease develops.

If you’ve ever wondered whether cancer runs in your family, or if a simple test could help you understand your personal risk, genetic cancer screening might be the answer. Here's what you need to know.

What Is Genetic Cancer Screening?

Genetic cancer screening is a type of test that looks for inherited gene mutations that increase the risk of developing certain types of cancer. Unlike diagnostic testing (which is used when symptoms or tumors are already present), genetic screening identifies whether you carry mutations in genes such as BRCA1, BRCA2, or MLH1, which are associated with breast, ovarian, colorectal, and other cancers [1].

These tests typically analyze DNA collected through a blood or saliva sample to detect mutations passed down through family lines. Identifying a hereditary cancer syndrome doesn’t mean you have cancer - it means you may be at a higher risk of developing it in the future [2].

What Types of Cancer Can Be Detected?

Genetic cancer screening can assess your inherited risk for many cancers. The most common include:

- Breast cancer

- Ovarian cancer

- Prostate cancer

- Colorectal cancer

- Pancreatic cancer

- Melanoma

- Endometrial (uterine) cancer

These cancers are often linked to inherited mutations in high-risk genes like BRCA1/2, TP53, and genes involved in Lynch syndrome (e.g., MLH1, MSH2, MSH6) [3].

Who Should Consider Genetic Cancer Screening?

You might consider genetic testing if:

- You have multiple family members with the same or related types of cancer

- Family members were diagnosed at a young age (typically under 50)

- A family member has a known genetic mutation

- You have Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry (which is associated with higher BRCA mutation rates) [4]

People with no known family history may still benefit from testing if their ancestry or personal history points to an elevated risk.

What’s Involved in the Testing Process?

Most genetic screening tests require a saliva sample or a small blood draw. The process is typically simple:

- Order a kit or visit a healthcare provider

- Collect and send your sample to a certified lab

- Review your results with a genetic counselor or physician

Genetic counseling is an essential part of this process, both before and after testing. Counselors help you understand whether testing is appropriate and interpret your results in the context of your medical and family history [5].

How Accurate Is Genetic Testing for Cancer?

Genetic cancer screening is highly accurate in identifying known mutations, with some tests detecting variants with over 99% sensitivity [6]. However, accuracy doesn’t mean certainty: testing only evaluates the genes included in the panel and cannot predict if or when cancer will occur.

A positive result means you have a mutation associated with increased risk - not that you will definitely get cancer. Similarly, a negative result does not eliminate all risk, especially if your family history is complex or unclear [7].

Benefits of Genetic Cancer Screening

The benefits of genetic testing go beyond peace of mind. Knowing your genetic risk can:

- Help you catch cancer early, when it’s most treatable

- Inform screening and prevention strategies (e.g., earlier mammograms or colonoscopies)

- Guide decision-making around lifestyle or surgical options

- Enable family members to get tested and take preventive steps [8]

By turning genetic insights into action, you can take control of your health before problems arise.

Pros and Cons of Genetic Testing

Pros:

- Informs proactive health decisions

- Helps you qualify for earlier or more frequent screenings

- Can lead to lifesaving interventions

- Offers valuable insight for your children and siblings

Cons:

- May cause emotional distress or anxiety

- Can lead to difficult family conversations

- Insurance coverage and genetic cancer screening cost may vary

- May not detect all mutations related to cancer [9]

It’s essential to weigh these factors with a qualified healthcare provider or counselor.

Cost of Genetic Cancer Screening

The cost of genetic cancer testing can vary widely. Some basic panels may cost a few hundred dollars, while more comprehensive tests can run over $2,000. Fortunately, many insurance plans now cover genetic testing for individuals who meet medical criteria, such as a personal or family history of cancer [10].

Several companies - including hospitals, commercial labs, and telehealth services - offer at-home tests that are more affordable and convenient. Still, always check whether the test is CLIA-certified and whether genetic counseling is included.

Genetic Counseling and Interpreting Results

Understanding genetic test results can be complex. A genetic counselor can help you:

- Make sense of your results

- Weigh medical and personal implications

- Discuss screening or risk-reducing options

- Share information with family members who may also be at risk

If a mutation is detected, your provider may recommend further screening, lifestyle changes, or preventive treatments based on established medical guidelines [11].

Can You Get Genetic Cancer Screening at Home?

Yes, several companies now offer at-home genetic cancer screening. These tests involve a simple saliva sample mailed to a lab and reviewed by physicians. While not all home kits are as comprehensive as clinical tests, they are a good option for people who want to start exploring their genetic health in a private, accessible way [12].

FAQs: Common Questions About Genetic Cancer Screening

How do I know if I should get genetic testing for cancer?

You may benefit from genetic testing if you have a strong family history of cancer, especially if relatives were diagnosed at a young age, or if a known genetic mutation (such as BRCA1 or BRCA2) runs in your family. Genetic counseling can help determine if testing is appropriate for you.

What types of cancer can be linked to genetic mutations?

Inherited mutations are most commonly linked to cancers such as breast, ovarian, prostate, colorectal, pancreatic, and endometrial (uterine) cancer. These cancers are often associated with well-known gene syndromes like BRCA and Lynch syndrome.

What happens if I test positive for a cancer-related gene mutation?

A positive result means you have an inherited mutation that may increase your risk for cancer. It does not mean you currently have cancer. Your doctor or genetic counselor will guide you through next steps, which may include more frequent screenings or preventive measures.

Are there any downsides to genetic cancer screening?

Yes. Potential drawbacks include emotional stress, concerns about privacy, uncertainty in results, and the possibility of discovering mutations of uncertain significance. It's important to receive counseling before and after testing to understand the implications.

Does a negative genetic test mean I won’t get cancer?

No. A negative result means the test didn’t find any of the mutations it screened for. However, you may still be at risk for cancer due to environmental factors, lifestyle, or undetected genetic causes. Routine cancer screenings are still recommended.

Can genetic testing help prevent cancer?

While it doesn’t prevent cancer directly, genetic testing empowers people to take preventive actions such as earlier screening, lifestyle changes, or preventive treatments, which can significantly lower the risk of developing cancer.

Taking Charge of Your Genetic Health

Knowing your genetic risk for cancer can be a powerful first step in managing your health. Whether you have a strong family history or are simply curious about your inherited risk, genetic cancer screening offers actionable insights that can lead to early detection and prevention.

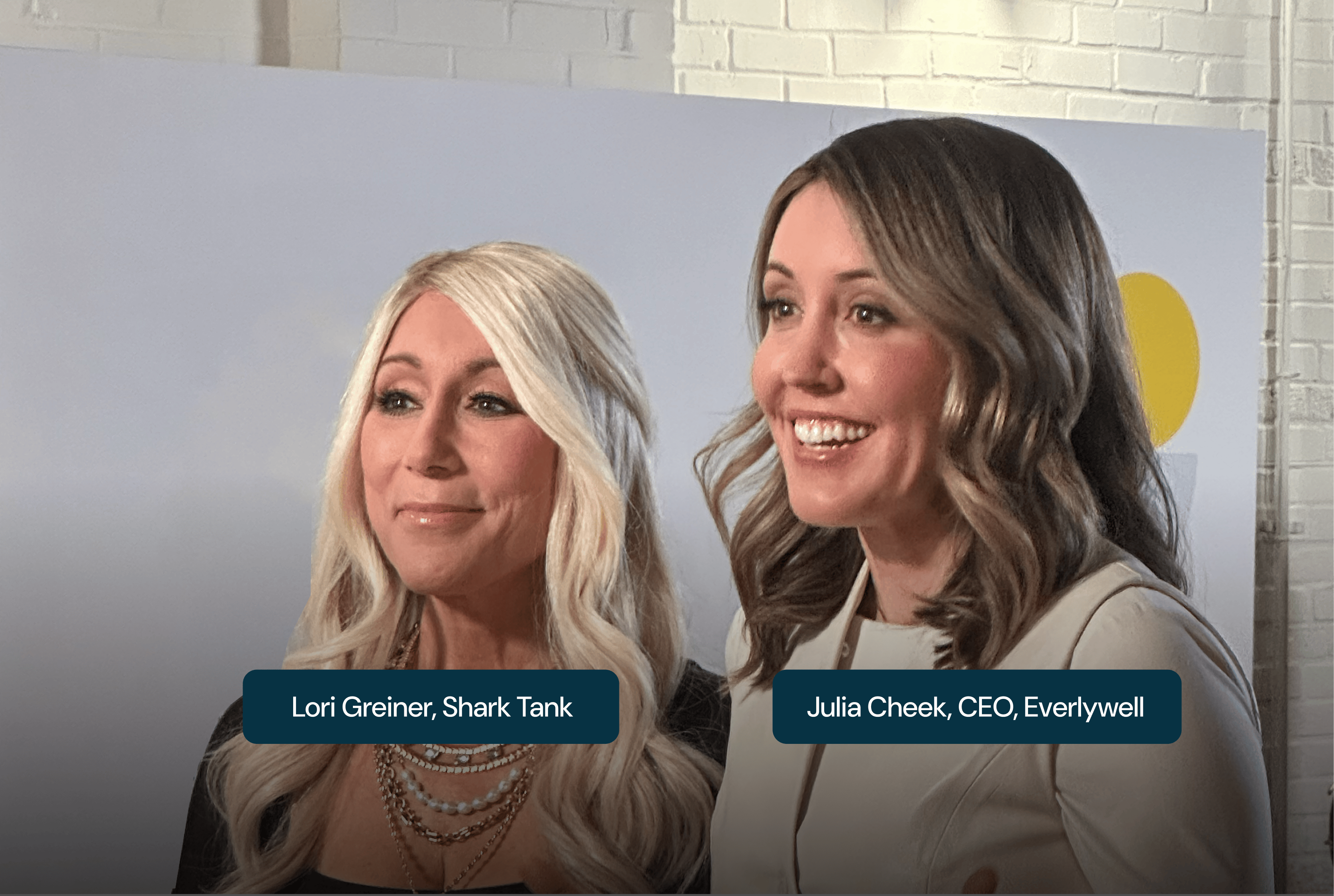

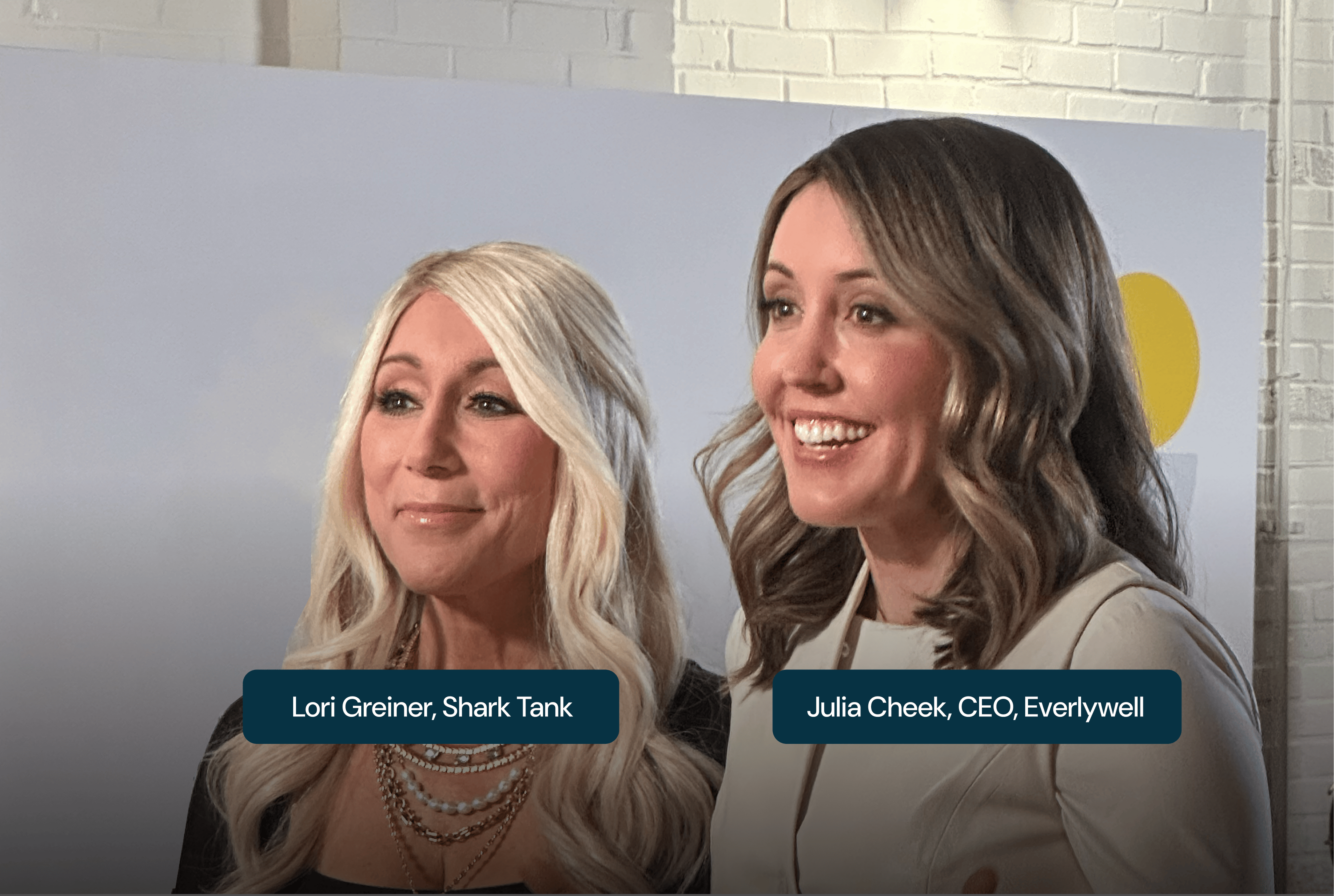

How Everlywell Can Help

At Everlywell, we believe knowledge is one of the most powerful tools for prevention. While we do not currently offer comprehensive hereditary cancer panels, we do offer at-home lab tests that empower you to understand your health on your terms.

Our test kits are discreet, physician-reviewed, and easy to use, so you can take action with confidence. Explore our health tests today to take the next step toward proactive wellness.

References

- American Cancer Society. Understanding Genetic Testing for Cancer. American Cancer Society. Published 2023. Accessed July 2, 2025. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/risk-prevention/genetics/genetic-testing-for-cancer-risk/understanding-genetic-testing-for-cancer.html

- National Cancer Institute. Genetic Testing for Cancer: Questions and Answers. National Institutes of Health. Updated May 24, 2024. Accessed July 2, 2025. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/genetics/genetic-testing-fact-sheet

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hereditary Cancer Syndromes. Updated May 30, 2023. Accessed July 2, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/genomics/disease/cancer/hereditary.htm

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Risk Assessment, Genetic Counseling, and Genetic Testing for BRCA-Related Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2019;322(7):652–665. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/brca-related-cancer-risk-assessment-genetic-counseling-and-genetic-testing

- Cleveland Clinic. Genetic Testing for Cancer Risk. Cleveland Clinic. Accessed July 2, 2025. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diagnostics/23972-genetic-testing-cancer-risk

- Invitae. Hereditary Cancer Testing. Invitae Corporation. Accessed July 2, 2025. https://www.invitae.com/us/providers/test-catalog/hereditary-cancer

- Yale Medicine. Genetic Testing for Hereditary Cancer. Yale School of Medicine. Published October 6, 2021. Accessed July 2, 2025. https://www.yalemedicine.org/news/genetic-testing-for-hereditary-cancer

- MD Anderson Cancer Center. How to Get Genetic Testing for Cancer. The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Published October 3, 2022. Accessed July 2, 2025. https://www.mdanderson.org/cancerwise/how-to-get-genetic-testing-for-cancer.h00-159459267.html

- Myriad Genetics. Hereditary Cancer Testing. Accessed July 2, 2025. https://myriad.com/

- JScreen. Hereditary Cancer Screen. JScreen Genetic Testing. Accessed July 2, 2025. https://www.jscreen.org/product/hereditary-cancer-screen/

- Color. Genomics for Individuals. Color Health, Inc. Accessed July 2, 2025. https://www.color.com/individuals-genomics

- Natera. Empower Hereditary Cancer Test. Natera, Inc. Accessed July 2, 2025. https://www.natera.com/oncology/empower-hereditary-cancer-test/

Get started

Latest offers

Explore Everlywell